Advanced Project Management of Kenya’s Urban Transport

Organisational Context

Introduction and Project Overview

Kenya’s urban transport sector has suffered from chronic underinvestment for decades, resulting in a deteriorating quality of public transport, extreme congestion, and mounting environmental concerns. The Kenya’s Urban Mobility Improvement Project (KUMIP), officially launched in July 2024, was designed as a flagship intervention to tackle these systemic challenges. Supported by a US$670 million World Bank and IDA financing package, KUMIP aims to overhaul urban mobility in Nairobi and the surrounding metropolitan areas.

KUMIP is not limited to a simple commuter rail upgrade. It comprises multi-sectoral components designed to reinforce each other: mass transit system improvements, green mobility initiatives, transit-oriented development (TOD), and institutional capacity building.

The lead implementing agency is the Kenya Railways Corporation (KRC), governed by the Kenya Railways Corporation Act (Cap. 397). Additional stakeholders include the Ministry of Roads and Transport, the Nairobi Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (NaMATA), and various county governments.

Read more: Advanced Project Management of the Climeworks

Organisational Strategy and Its Influence on Project Success

KUMIP is strategically aligned with Kenya’s long-term national development plans, notably Vision 2030 and the Nairobi Metro 2030 Strategy. Vision 2030 outlines the goal of making Kenya a middle-income economy by enhancing infrastructural capacity and social equity. Urban mobility, particularly commuter rail, is emphasized as a flagship sector to support economic productivity and reduce social inequalities.

From a project management perspective, strategic alignment is often considered a critical success factor. If a project fails to fit into an organisation’s or a country’s broader strategy, it is likely to face resource constraints, political pushback, or sustainability risks.

However, in KUMIP’s case, the project’s alignment with Vision 2030, the Sustainable Urban Mobility Policy (under preparation), and Kenya’s climate commitments positions it favourably.

That said, over-alignment with government agendas can sometimes cause rigidity, reducing project flexibility when unexpected challenges arise. For example, the political prioritisation of the Nairobi Central Station to the Ruiru commuter rail corridor may unintentionally overshadow other critical transport needs in Nairobi, such as informal sector integration or matatu reform. Therefore, while strategic alignment is necessary, it must be balanced with adaptive project management.

Organisational Structure and Institutional Complexity

KUMIP operates within a highly fragmented institutional framework. Multiple agencies are involved: KRC, NaMATA, State Department of Transport, State Department of Roads, Nairobi City County, and Kiambu County. While the establishment of a Project Management Office (PMO) under Component 3.2 aims to streamline coordination, such a complex structure inherently carries risks of miscommunication, duplication of efforts, and bureaucratic delays.

Organisational structure in project management directly affects decision-making speed and project agility. KUMIP uses a hybrid governance model involving both vertical (national-level ministries) and horizontal (county governments, NaMATA) actors.

While this supports multi-stakeholder ownership, it complicates accountability. Research by warns that when governance structures are too diffuse, projects face higher risks of role ambiguity and scope creep.

Moreover, the central role of KRC, a parastatal with historical inefficiencies, could potentially slow implementation. KRC’s prior struggles with project execution and procurement delays are well-documented. The risk here is that KUMIP’s ambitious scope might overwhelm KRC’s current capacity despite planned institutional strengthening measures.

Organisational Culture

Kenya’s public sector traditionally operates within a hierarchical and compliance-driven culture. This can conflict with the flexible, user-focused culture required for successful urban mobility projects. KUMIP introduces innovative elements such as e-mobility pilots, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), and Integrated ICT fare systems. These initiatives demand a shift in organisational mindset from infrastructure provision to service delivery and customer experience.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions suggest that high power distance and uncertainty avoidance can stifle innovation. For KUMIP, a bureaucratic culture may resist changes like public-private partnerships (PPPs) for station area development or the introduction of land value capture (LVC) tools, which require new skills and inter-agency cooperation.

To overcome this, change management strategies must be embedded within KUMIP’s capacity-building components. As noted by, leadership must create a sense of urgency for cultural transformation and empower lower-level managers to take initiative. The ongoing efforts to reform KRC’s Commuter Rail Unit and update the Kenya Railway Training Institute’s curriculum are steps in the right direction, but require continuous monitoring.

Governance Frameworks and Accountability Mechanisms

KUMIP’s governance is framed around a World Bank-financed project governance model that includes environmental and social safeguards, procurement transparency, and stakeholder engagement plans. These are necessary but not sufficient conditions for project success.

Drawing from the Project Governance Model (Bekker & Steyn, 2009), KUMIP requires clear delineation of roles between project governance (decision-making, strategic oversight) and project management. Currently, this line is blurred. For example, while the State Department of Roads is tasked with policy, it also manages procurement elements under Component 3.2, creating potential for conflicts of interest.

Public participation is another governance pillar. Kenya’s Constitution (2010) mandates stakeholder engagement, and KUMIP’s Stakeholder Engagement Plan (SEP) explicitly incorporates this. However, meaningful engagement must go beyond consultation workshops.

As per, genuine stakeholder involvement should include co-design and shared decision-making, especially given the project’s impact on low-income communities reliant on informal transport.

There’s also a risk of governance capture, where powerful interests, such as landowners near stations, could disproportionately benefit from TOD initiatives if land value capture mechanisms are not equitably designed. Therefore, governance systems must incorporate anti-corruption safeguards and transparent revenue-sharing models.

Recommendations for Improvement

- Strengthen Adaptive Capacity: Embed adaptive project management tools (e.g., rolling-wave planning) to respond to emerging challenges without rigid adherence to initial plans.

- Clarify Governance Lines: Establish clear boundaries between policy oversight (ministries) and project delivery (KRC/PMO) to reduce decision-making conflicts.

- Promote Organisational Learning: Use KUMIP as a platform for developing Kenya’s urban transport management capabilities, including promoting agile leadership and cross-sectoral collaboration.

- Enhance Inclusivity: Expand stakeholder engagement from consultation to collaboration, ensuring vulnerable groups have decision-making input, not just feedback opportunities.

- Safeguard Against Elite Capture: Design land value capture policies that include community benefit sharing to prevent TOD benefits from accruing only to wealthy landowners.

Kenya Urban Mobility Improvement Project (KUMIP) is very important initiative in transforming urban mobility in Nairobi and its surroundings. The project has massive potential in addressing some of the ancient issues, including congestion, poor transport system, and environmental degradation, in the country with a good financial support, and as per the vision 2030 of Kenya.

However, the path to success is not a smooth ride. The pace of progress is also threatened by institutions, bureaucratic culture, and the risk of vague governance and elite capture because of the involved complex web of institutions. To ensure that KUMIP is truly effective, it is not just a requirement that one invests in it, but also that they have flexible planning, clear leadership positions, transparent and participatory stakeholder involvement and change of attitude towards innovation and service delivery.

Through capacity building of the most relevant organisations, promotion of partnership and ensuring equitable benefits to all, including vulnerable communities, KUMIP can emerge as a role model of sustainable and inclusive urban mobility in Kenya and beyond.

Project Selection Best Practice for KUMIP

Introduction:

The selection of the project is a basic process of project management, particularly in large-scale infrastructure projects such as the Kenya Urban Mobility Improvement Project (KUMIP). Theoretically, the selection of projects is supposed to be an objective procedure driven by the strategic fit, feasibility, and quantifiable results.

Practically, however, the process of choosing such projects as KUMIP is complicated and depends on the national development priorities, political factors, and institutional environment.

KUMIP is a perfect illustration of conflicts between international best practice in project selection and the practicalities of governance in the public sector in developing economies.

The project will modernize the commuter rail system in Nairobi, implement green transportation options, and improve traffic control, and the overall objective is to improve urban mobility in Kenya.

Global Best Practices in Project Selection:

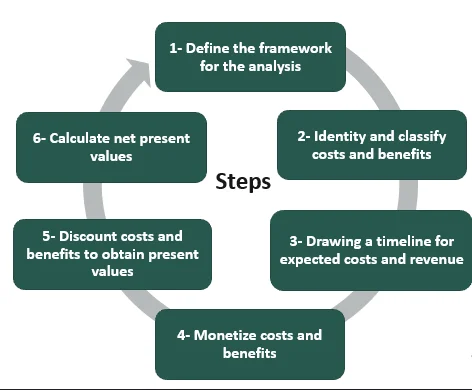

Different organisations have a variety of project selection methods that they use around the world such as cost-benefit analysis (CBA), multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), real options analysis and strategic alignment models. The method usually depends on the sector, the size of the project, and organisational maturity.

In the field of public infrastructure, especially in developing nations, CBA still reigns supreme. As

state, CBA enables policy-makers to measure anticipated benefits, including less congestion, time savings, and environmental benefits, and compare them with costs. However, opponents claim that CBAs may underestimate the social and environmental effects, particularly where the benefits are difficult to quantify.

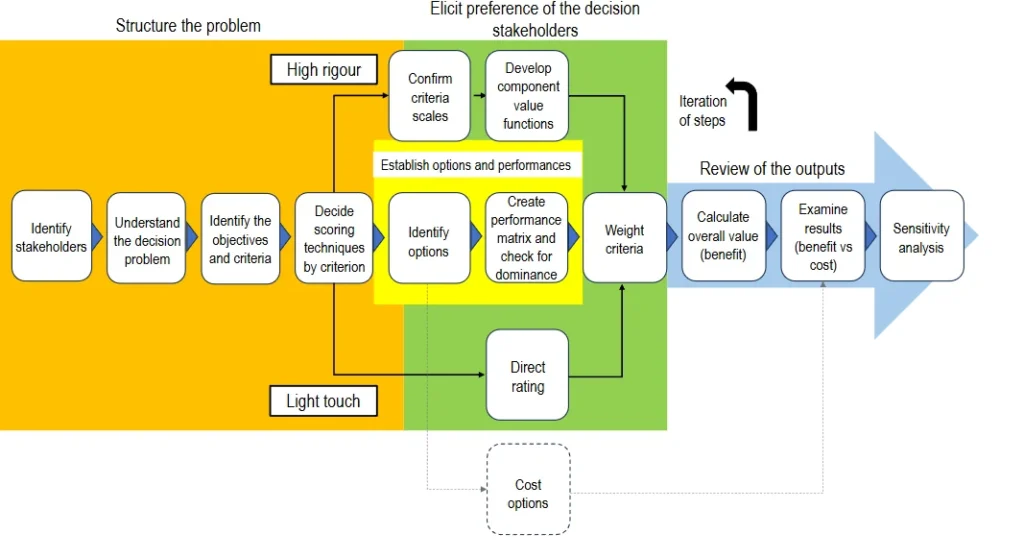

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) has become a more comprehensive tool, which takes into consideration qualitative elements, including social equity, political feasibility, and institutional readiness. MCDA allows governments to consider trade-offs between competing goals, such as economic efficiency and social inclusion.

In the urban transport sector, international best practices also emphasize the need for participatory planning. As per, successful transport projects should align with Sustainable Development Goal 11, which focuses on making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Public engagement and stakeholder participation are therefore considered essential, though not always practiced effectively.

How Organisations Determine Context-Appropriate Methods:

Selecting the right project selection approach is context-dependent. In Kenya, the devolved governance system complicates decision-making. National agencies like the Ministry of Roads and Transport and the Kenya Railways Corporation (KRC) lead on technical design, while county governments manage land use and local infrastructure.

KUMIP’s selection was guided primarily by strategic alignment with Kenya Vision 2030, Nairobi Metro 2030, and emerging climate policies. This aligns with the strategic fit model of project selection, where projects that match long-term development goals are prioritized.

However, strategic alignment alone can lead to project prioritization that overlooks immediate local needs or operational constraints. Nairobi’s commuter rail, for example, has historically underperformed due to poor service frequency and limited coverage. Despite this, KUMIP prioritizes expanding the rail network. The risk is that investments may not yield expected modal shifts if systemic service issues persist.

KUMIP also incorporates feasibility analysis through the procurement of technical studies. In March 2025, KRC launched tenders for consultancy services to conduct feasibility studies and engineering designs for rail upgrades. This is consistent with international norms, where pre-investment analysis helps validate project assumptions.

Yet, the timing is problematic. The feasibility studies are happening after project approval, not before. This sequence reduces the utility of the studies in actual project selection, turning them into justifications rather than decision-making tools. As Flyvbjerg notes, this approach often leads to “optimism bias,” where benefits are overestimated and costs underestimated.

KUMIP’s Approach to Project Selection:

KUMIP’s selection methodology reflects a blend of global best practices and political realities. The project’s focus on commuter rail aligns with international urban mobility trends, promoting mass transit and low-carbon solutions. However, this approach may not fully address Nairobi’s actual mobility patterns, where over 70% of commuters rely on informal minibuses (matatus).

While the project attempts to integrate rail with BRT and matatu services via NaMATA, coordination remains a challenge. Historically, Nairobi’s transport planning has been siloed, with roads, rail, and public transport managed by different agencies.

KUMIP tries to bridge this gap by establishing a Project Management Office (PMO) within the State Department of Roads. Nonetheless, inter-agency coordination risks remain, especially since procurement and policy decisions cross multiple jurisdictions.

Another issue is the lack of a formal MCDA application. Although KUMIP includes multiple components, rail, traffic management, green mobility, the decision to focus primarily on the Nairobi–Ruiru line appears driven more by strategic and political considerations than by a balanced assessment of all alternatives.

Moreover, while public consultations occurred during project preparation, the depth of stakeholder engagement is debatable. As per, genuine participation requires co-creation of solutions, not just information sessions. KUMIP’s consultations, while compliant with World Bank guidelines, may not fully reflect the needs of all commuter demographics, particularly informal sector users.

On procurement, KUMIP aligns with global best practice by using open international bidding, adhering to World Bank and Kenyan Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act guidelines. This promotes transparency and reduces corruption risks. However, large international tenders can sometimes marginalize local firms and reduce local capacity building, an issue noted by.

Recommended Project Selection Model for KUMIP:

Given the complexity of KUMIP, a hybrid project selection model combining Strategic Alignment, MCDA, and Portfolio Management would be more appropriate.

Strategic Alignment:

Maintain alignment with Vision 2030 and climate goals, but embed flexibility to adapt to new priorities.

MCDA:

Use a formal MCDA framework to weigh multiple factors, economic returns, social inclusion, gender equity, environmental benefits, and institutional readiness.

Portfolio Management Approach:

Treat KUMIP as a program rather than a single project, with phased investments and iterative reviews. This allows for resource reallocation if certain components underperform.

For example, if the commuter rail ridership targets lag, resources could shift toward enhancing feeder services or upgrading informal transport rather than persisting with underused rail expansions.

The Kenya Urban Mobility Improvement Project (KUMIP) is a daring and long-overdue initiative to enhance the transport system in Nairobi, but its project selection process indicates noteworthy gaps. The project is in the right direction as it complies with national priorities such as Vision 2030 and a lot of international best practices, such as open procurement and feasibility studies.

But others, such as the decision to give priority to the commuter rail, appear to have been taken without careful study or widespread consultation. The existing strategy threatens to ignore the actual transport requirements of the majority of Nairobi residents, in particular, users of informal matatu services. To enhance the selection of future projects, KUMIP needs to implement a hybrid model that combines strategic alignment, formal MCDA (Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis), with a portfolio-based approach.

This would enable the technical, social, and economic factors to be better balanced and yet keep the project flexible and responsive. Ultimately, the more open, inclusive and flexible selection will ensure that KUMIP will not only result in a change that will benefit all urban commuters but not just a small number.

Building and Leading Successful Project Teams for KUMIP

Introduction:

The success of the implementation of the complex infrastructure projects, such as the Kenya Urban Mobility Improvement Project (KUMIP), is not only determined by the financial and technical inputs but also by the leadership and teamwork arrangements.

By 2025, KUMIP is in the early stages of implementation, which implies both the achievement of operational milestones and major challenges in terms of inter-agency coordination, management of stakeholders, and scope control. These problems highlight the importance of good leadership and well-knit project teams.

This assignment critically analyses the leadership and teamwork elements that affect the performance of KUMIP. It also outlines how the project manager can adapt leadership styles, referencing key theories such as Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Leadership Model, Tuckman’s Team Development Stages, and Belbin’s Team Roles to navigate the project’s complex landscape.

Key Factors in Leadership and Teamwork Impacting KUMIP:

Leadership Style and Flexibility:

Leadership in large infrastructure projects is not a one-size-fits-all exercise. KUMIP is a multi-stakeholder initiative involving public agencies, private contractors, civil society, and international financiers. This diversity necessitates an adaptive leadership approach. For example, during the stakeholder engagement process, KRC officials had to manage sensitive community concerns about land acquisition and resettlement, particularly along the Nairobi–Thika corridor.

In this context, an authoritarian or transactional style would have been counterproductive, risking community backlash and legal challenges as seen in the Karen suburb lawsuit over the Riruta–Ngong line.

Conversely, KUMIP’s coordination with Nairobi Railway City and BRT initiatives requires assertive and decisive leadership to ensure alignment across projects with overlapping scopes. Here, delays in one project can create cascading problems for another. This demands a project leader capable of managing both consensus-building and authoritative decision-making depending on the scenario.

Team Composition and Role Clarity:

KUMIP involves a consortium of local and international consultants, government officials, and community representatives. Belbin’s Team Roles Model highlights the need for balanced roles, implementers, coordinators, shapers, and completer-finishers, to ensure functional teams. However, in public sector projects like KUMIP, role ambiguity is a common risk.

The existence of multiple overlapping agencies, KRC, NaMATA, KURA, and county governments, means responsibilities can become blurred, potentially leading to duplication of work or decision paralysis.

Communication and Cultural Sensitivity:

Effective communication is a cornerstone of successful teamwork. KUMIP’s Stakeholder Engagement Plan (SEP) includes mechanisms for grievance redress and public information sharing. However, cultural barriers and historical distrust of government projects in Kenya pose risks to transparent communication. In past projects, communities have often felt marginalized during the planning stages. KUMIP must proactively counteract this by embedding inclusive dialogue processes.

Conflict Management and Emotional Intelligence:

Large infrastructure projects are prone to conflicts, whether between contractors, government bodies, or community members. KUMIP’s overlapping timelines with Nairobi’s BRT and Railway City development increase this risk. According to, emotional intelligence (EI) is critical for leaders managing high-stakes, multi-party environments.

EI enables the project manager to anticipate tensions, mediate disputes, and maintain team morale, especially when project phases like land acquisition or resettlement action plans become contentious.

Application of Leadership Theories:

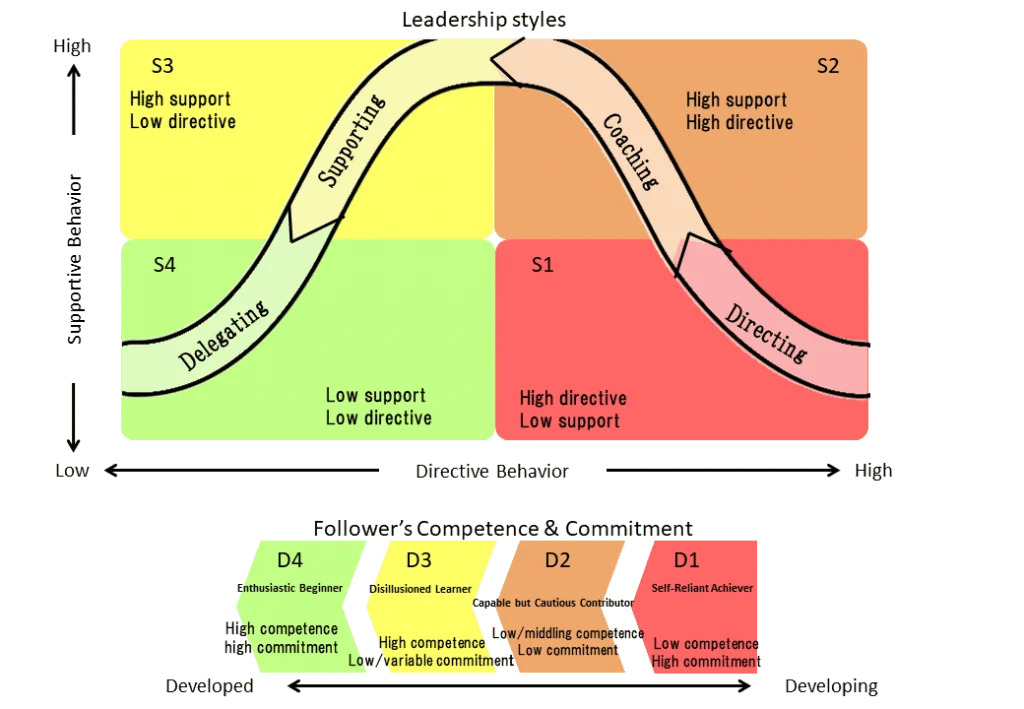

Situational Leadership Model:

Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Leadership Model (1988) provides a useful framework for KUMIP’s project manager. The model advocates adjusting leadership style based on the team’s competence and commitment.

Directing:

For new team members, such as recently hired local consultants unfamiliar with World Bank protocols, the project manager should adopt a directive style, providing clear instructions on procurement and reporting procedures.

Coaching:

For the coordination with NaMATA and KURA, where there is institutional knowledge but limited experience in integrated transport systems, a coaching approach can foster learning while maintaining guidance.

Supporting:

When dealing with county governments and community representatives, the project manager should prioritize supportive leadership, facilitate participatory planning, and encourage stakeholder ownership.

Delegating:

For specialized tasks like ERP system development, where external ICT experts are leading, the project manager should adopt a delegating style, trusting the specialists to deliver while providing strategic oversight.

This flexible leadership approach reduces the risk of team disengagement and ensures responsiveness to dynamic project conditions.

Tuckman’s Team Development Stages:

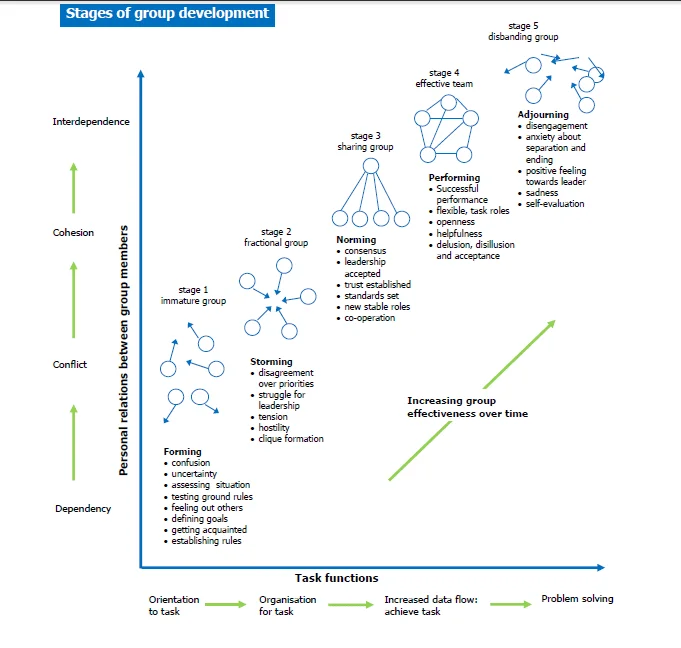

KUMIP’s team dynamics are likely evolving through Tuckman’s (1965) stages of team development: Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing, and Adjourning.

Forming:

Initial stakeholder meetings and the recruitment of consultants represent the forming phase, where team members are oriented to goals.

Storming:

Conflicts may arise during resource allocation or role negotiation, especially between national and county entities.

Norming:

Establishing clear protocols via the Project Management Office (PMO) can help the team stabilize.

Performing:

By 2026, when civil works begin, the team must operate at high efficiency, resolving issues quickly to avoid delays.

Understanding these stages helps the project manager anticipate and manage team dynamics effectively.

Recommendations to Avoid Failure from Poor Leadership and Teamwork:

Enhance Collaborative Decision-Making:

The project manager should implement regular joint planning sessions, bringing together KRC, NaMATA, KURA, and county representatives to review timelines and resolve bottlenecks. This avoids the siloed decision-making that has historically plagued Nairobi’s transport sector.

Institutionalize Knowledge Sharing:

Creating a knowledge management system, possibly integrated into the ERP platform, will help document lessons learned, such as the experiences from the Karen lawsuit over stakeholder engagement. This prevents repeated mistakes in future phases.

Build Emotional Intelligence and Soft Skills:

Leadership development programs focusing on emotional intelligence and conflict resolution should be mandatory for senior project leaders. As per, these skills are essential in complex, politically sensitive projects.

Develop a Contingency Management Plan:

Given the risks from climate events and political unrest, KUMIP’s leadership must plan for disruptions. For example, scheduling earthworks in dry seasons and developing protocols for protest-related shutdowns can mitigate delays.

Clarify Operational Leadership Post-Construction:

The project should also make it clear at an early stage whether KRC will run the commuter rail service or contract a private operator. Insufficient clarity might affect the sustainability of operations, which was experienced in previous failures of public transport in Kenya.

To sum up, money, infrastructure, or policy are not the only factors of the success of KUMIP, but also the presence of strong leadership and effective teamwork. As the number of stakeholders involved is great, including government agencies and local communities, good leadership should be adaptive and open.

The project manager must be able to change his style according to the situation- whether it is providing clear instructions, coaching, supporting, or letting the experts do their job. It is equally important to build strong and well-balanced teams with defined roles.

Team development stages, such as those described by, and team roles as described by, can be used to help teams work together more effectively over time. Communication skills and emotional intelligence play an important role in avoiding conflict and maintaining relationships, particularly when hard topics such as land acquisition arise.

Lastly, transparent cooperation, frequent knowledge exchange, and effective decision-making processes will prevent typical project trappings in KUMIP. KUMIP can emerge out of its complicated issues and provide a more connected, inclusive, and efficient transport system in Nairobi with the right leadership approach.

Project Planning and Scheduling Techniques for KUMIP

Introduction:

Project planning and scheduling play a central role in the success or failure of large-scale infrastructure projects. In the case of the Kenya Urban Mobility Improvement Project (KUMIP), planning is not just a bureaucratic process; it is needed to prevent cost overruns, delays, and public outcry.

By 2025, KUMIP is still in its pre-construction stage, with issues of multi-agency coordination, budgetary limitations, and political influence being a problem.

Since the project is rather complex (it involves commuter rail modernization, green mobility projects, and institutional change projects), the choice of planning and scheduling methods needs to be critically evaluated. This task compares two dominant approaches: Waterfall (Traditional Project Management) and Agile (Adaptive Project Management). It also speaks of Critical Path Method (CPM) and Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM), and suggests a hybrid approach that suits the needs of KUMIP.

Waterfall Methodology:

The waterfall model is a phase-wise, sequential approach that is commonly applied in infrastructure development, where feasibility, design, procurement, construction, testing, and commissioning are in sequence.

Strengths:

Waterfall has advantages to KUMIP, such as clarity and control with the detailed documentation, which is valuable to address the regulatory requirements such as EIAs, and upfront alignment of stakeholders on the scope and budget, which is essential in coordination among KRC, county governments, and the World Bank. It is also suitable in physical infrastructure, where design modifications are expensive.

Weaknesses:

Nonetheless, its inflexibility is a disadvantage in dynamic environments such as Nairobi, where political instability or floods may derail schedules. Feedback delays may cause the omission of such issues as last-mile connectivity, and even though Waterfall is highly structured, it is still susceptible to scope creep in case of political pressure.

Agile Methodology:

Agile focuses on iterative development, continuous feedback, and adaptive planning. While traditionally used in software, Agile is increasingly applied in infrastructure projects, especially in policy and technology integration components.

Strengths:

Agile adds flexibility to KUMIP, enabling it to adapt to real-time problems such as BRT delays or land acquisition problems. Its focus on constant involvement of stakeholders prevents conflicts, which is evident in the Karen suburb conflict. Agile is also compatible with ICT parts of KUMIP, including ERP and fare systems, which can take advantage of iterative design.

Weaknesses:

Nevertheless, Agile is not as applicable to heavy civil projects such as rail construction, where engineering sequences must be fixed. It also exposes itself to scope creep and late delivery, considering that KUMIP will be closely integrated with Railway City and BRT. Also, Kenya procurement laws incline towards strict scopes and this reduces the use of Agile.

Critical Path vs. Critical Chain Scheduling:

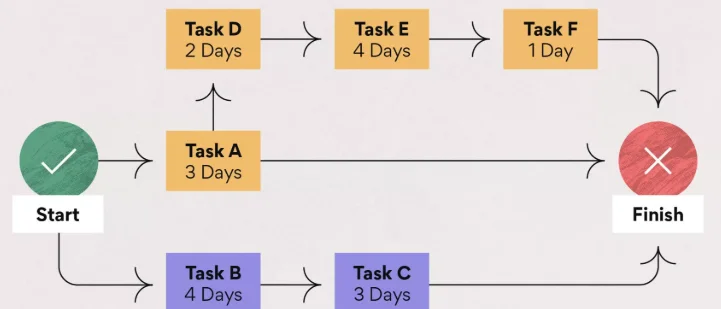

Critical Path Method (CPM):

Critical Path Method (CPM) is a project scheduling tool used to identify the longest chain of interdependent activities (the critical path) that determines the minimum amount of time needed to complete a project.

When there is a delay in any activity in the critical path, the entire completion of the project is delayed. CPM is a widely applied method in construction and infrastructure because it is a structured, time-based methodology.

Advantages:

Clear Timeline Focus:

CPM helps in the accurate ordering of tasks, including land acquisition, feasibility studies, procurement, civil works, system installation, and commissioning. In the case of KUMIP, this will mean that the interdependent activities, such as upgrading of rail infrastructure and construction of stations, will be logically sequenced and checked for delays.

Milestone Monitoring:

CPM offers the project managers a clear tracking of milestones, which enables them to visualize the dependencies and establish accountability of each phase. This is especially important in KUMIP, where it should be integrated with the BRT system in Nairobi, so that commuter rail operations should be coordinated to prevent gaps in commuter services.

Disadvantages:

Resource Blindness:

CPM is concerned with the order of tasks but does not consider resource availability, including labor, materials, and equipment. This is a tangible threat in Kenya because of the lack of local contractors, the overstrained capacity of the railway construction, and the disruption of the global supply chains in terms of the delivery of rolling stock.

Brittleness to Delays:

CPM supposes that every important task will be carried out continuously. Nevertheless, political cycles, land conflicts, and climate risks (e.g., flooding) in Kenya can cause unforeseen delays. As a case in point, the Nairobi Ruiru Line has previously been stalled because of political demonstrations.

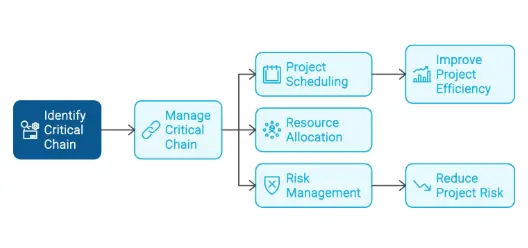

Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM):

public transport is a contribution by to CPM, which directly considers the resource constraints and project buffers in the scheduling. In contrast to CPM, CCPM focuses on controlling the flow and capacity of projects, as opposed to task timing.

Advantages

Focus on Resource Availability:

CCPM acknowledges the fact that resources are frequently shared among projects and adds resource dependencies to the scheduling logic. In the case of KUMIP, where the specialized railway engineers, imported equipment, and a few construction companies work on parallel projects (like the BRT expansion in Nairobi), CCPM is more realistic in terms of real-world limitations.

Buffers for Uncertainty:

CCPM introduces time buffers at critical locations (e.g., project completion, critical handoffs) to absorb uncertainties. In the case of KUMIP, risks that can be countered by buffers include:

- Climate change (flooding in the process of track works)

- Political occurrences (elections or protests that delay the process of acquiring land)

- Supply chain problems (delays in the delivery of the rolling stock)

Disadvantages:

Requires Cultural Change:

CCPM demands a shift from task completion to resource flow management, which may face resistance in Kenya’s traditional public sector project management culture.

Complex Implementation:

Establishing realistic buffers and managing them effectively is complex and requires skilled project managers, which may be in short supply.

Recommendations for KUMIP:

Given KUMIP’s hybrid nature, combining infrastructure, technology, and policy, the following planning and scheduling strategy is recommended:

Adopt a Hybrid Waterfall-Agile Approach:

- Waterfall in civil works (e.g., rail rehabilitation, station construction) because of clarity of specs and sequencing.

- Agile on tech and policy elements (e.g., fare systems, ERP, institutional reforms), and with the ability to pilot and iterate.

This hybrid approach is increasingly recognized as best practice in complex projects.

Use Critical Chain for Scheduling:

More appropriate than CPM because of the resource limits and risks (protests, flooding) faced by KUMIP. CCPM buffers eliminate the possibility of delays derailing the progress, like political protests or climate-related flooding, that have already disrupted Nairobi’s transport projects.

Establish Rolling Wave Planning:

Implement Rolling Wave Planning, which means to plan short-term activities in detail, leave long-term plans open until more data (e.g., feasibility studies) becomes available by 2026.

Strengthen Monitoring and Adaptation Mechanisms:

Track and get feedback in real-time using the ERP tools. Dynamic schedule adjustments and resource reallocation e.g., buffer schedules in case of land acquisition problems.

The planning of KUMIP must be flexible and controlled. The hybrid of Waterfall-Agile with Critical Chain scheduling fits this complicated project, as it allows systematic infrastructure building and flexible management. Buffer management, phased planning and real-time monitoring will enable KUMIP to manage uncertainties better and achieve transformative urban mobility in Kenya.